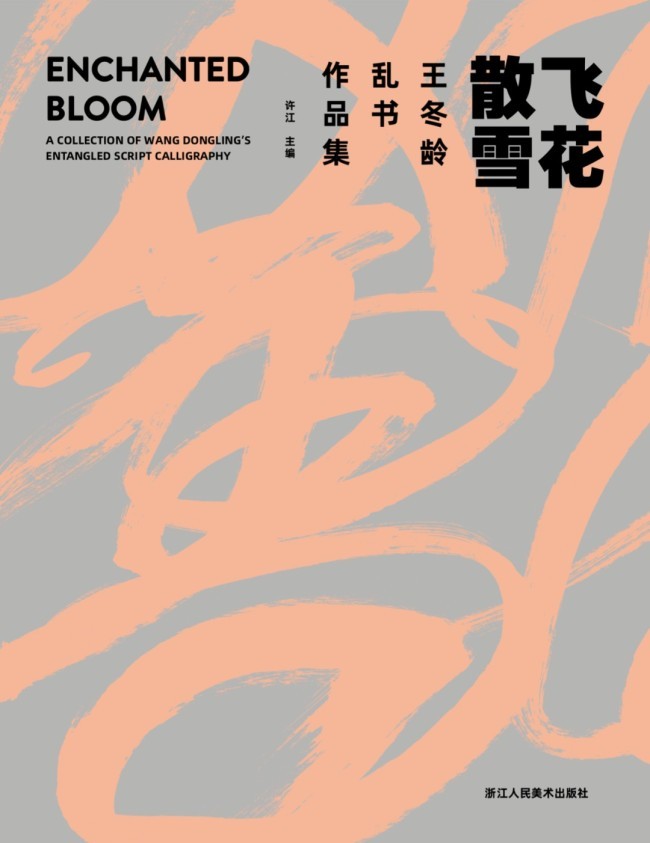

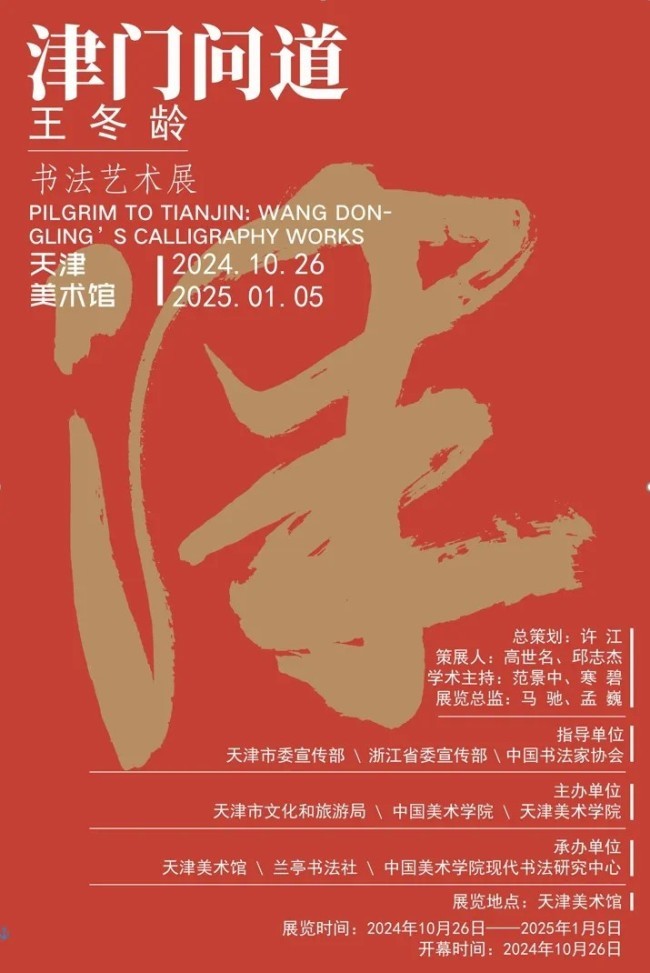

“津门问道——王冬龄书法艺术展”于2024年10月26日在天津美术馆开幕,展期至2025年1月5日。本文是北京画院院长吴洪亮为《飞花散雪·王冬龄乱书作品集》和“津门问道·王冬龄书法艺术展”所撰序言。原文如下——

不是一,不是二

——王冬龄的书法突围

故宫博物院有一幅名作《乾隆皇帝是一是二图》。图中乾隆皇帝着汉服坐于榻上,身后屏风上悬挂着一幅与乾隆容貌一样的画像。这一题材并非首创,古已有之,但乾隆对此有自己的思考。他在题跋中写道:“是一是二,不即不离。儒可墨可,何虑何思。”一般解释为乾隆试图表明自己对儒家、墨家的学说都可接受,体现出“求和为上”的观念。但当代艺术恐怕常常是相反而相成的。当受邀为王冬龄老师的新书写点什么时,我由这幅画想到了六个字——“不是一,不是二”,用来描述王老师的书法突围与大胆实践可能更为恰切。他的艺术不是为了确定自己“是什么”,而是通过种种实验来表明他“不是什么”。“不是一,不是二”这一表述是对“一”与“二”的解放,试图超越简单的二元对立思维,指向一种更为复杂、综合、开放的理解方式,进而强调非绝对性的价值,强调变化与发展,强调艺术的实践不是一种可以被量化或简单定义的东西。王冬龄就是这样一位实践者。因此,王冬龄虽已年近八旬,但其先锋性的探索依旧,故而也常被质疑。譬如:他的作品还是不是书法?如果是书法,书法的核心与外延在哪里?再譬如:王老师近年喜欢在全世界进行创作的现场表演,这是否破坏了书法艺术的严肃性?要回答这些问题,首先要进行一个简约版王冬龄创作历程的回溯。他自述的经历以书法为主线可分为三个阶段:第一阶段是1962—1979年,以各种书体的临摹为主,巩固书法根基;第二阶段是1980—2007年,在兼学诸家的基础上专攻草书,开创大字书法,探索书法的现代发展;第三阶段是2008年以后,尝试在不同媒介上使用多样的材料进行书写,将书法置入当代艺术语境,并创造出独具特色的乱书。在六十多年的书法生涯中,王冬龄经历了从中华人民共和国成立前期到十年动荡的波折,从计划经济向社会主义市场经济的转型,从信息化时代到智能化时代的发展。在时代的浪潮中,有些人选择以不变应万变,独善其身、自得其乐;有些人选择领风尚之先,跃出藩篱、潮头弄浪。王冬龄无疑属于后者。因此,考察他的创作历程,既要关注艺术本体语言上的创造,还要跳出来,从“不是什么”的维度进行审视。以此为前提,我们可以从三个角度进入王冬龄的艺术实践。

一、从传统突围

2012年,王冬龄的《春江花月夜》在“书写之道:八位中德艺术家上海联展”上展出,标志着他的乱书风格正式亮相。自此时起,这种极难识读的书体便饱受争议。其实,乱书只是一个结果,要真正理解其意义,须得寻踪溯源,厘清其发展逻辑。

王冬龄的书法天分毋庸置疑。1962年,十六岁的他以一幅小篆作品参加江苏省第二届书法印章展,成为最小的参展作者。其作品与林散之、高二适、胡小石等前辈名宿之书同堂陈列,成为一时佳话。追溯王冬龄的学书历程,除资质外,其机遇也是得天独厚的。1967年,经尉天池介绍,王冬龄拜入林散之先生门下,成为这位草书大家的入室弟子,为他日后得大草之真意奠定基础。1979年,他考入浙江美术学院(今中国美术学院)首届书法研究生班,成为陆维钊、沙孟海、诸乐三的学生,受沙孟海先生气势雄强的榜书影响甚大,为日后的大字实践埋下伏笔。

早年的书法学习经历为王冬龄打下了牢固的根基,乱书正是从此脉络中生长出来的。用他自己的话来说,乱书之“乱”,“其实就是破除了传统书法笔画不能交叉的铁律,现在不仅线条可以交叉,字与字还要重叠”。王冬龄曾将董其昌和徐渭的书法作对比,以揭示其乱书的传统逻辑。董其昌的书法讲究布局的规矩,左右行距分明,呈现出一种清贵、端庄的感觉,而徐渭则有意打破“行气”,弱化分行的概念。王冬龄在徐渭的基础上又往前走了一步,不但打破左右分行,而且让线与线、字与字相叠加,彻底突破了传统书法的结字方式和布局规范。与此同时,乱书的诞生也受到自然造化的影响。据说,唐代怀素草书的大成是从夏日涌动的云气中得到灵感,王冬龄的乱书则是受到了西湖残荷的启发。在中国美术学院的执教生涯让其有机会长期与西湖的荷为伴,而他最爱的便是残荷——那种一派枯寂却又蕴藏着再生生命力的气象对王冬龄产生极大震动。十多年来,他自己拍摄的残荷作品不下万张,这种观荷的体悟也在无形中浸润着他的书法。有观众看到王冬龄的巨幅乱书《千字文》,就自然而然地联想到西湖的接天残荷。从书法传统到自然造化,乱书的必然性和偶然性既顺理成章又颇具机缘。

乱书的诞生既有自洽的发展逻辑,也有鲜明的问题意识。人们多多少少都会意识到,有着数千年悠久历史的中国书法发展到今天,所处的环境已经发生了根本性的变化。笔、墨、纸、砚不再是书写的必要工具,书法从日常变成学科,书法家从兼职变为职业。在今天的艺术分类中,书法占据专门的一类,甚至被列入了世界非物质文化遗产名录。王冬龄很早就发现,只是沿袭传统书法的老路已经不能适应今天的时代发展。我们今天面对的问题不光是如何继承传统,更要考虑怎样让书法在当代环境中重现活力,乃至进一步发展。传统书法的当代转型,甚至“将竹子种在5G的时代”,这是包括王冬龄在内的诸多当代艺术家都在进行的尝试。王冬龄的思路是将书法视为水墨构成的根基,把狂草的磅礴气象与抽象水墨相勾连。乱书的学理依据和当代特征即在于此。当文字的识别难度大幅提升,它的表意功能就随之弱化,书法本身的造型、线条、布局等则更加凸显。至此,书法化身为有意味的形式,超越传统的审美范畴而向另一个维度的抽象艺术美学演进。两千多年前,赵壹在《非草书》中所批判的草书超越实用功能的特点,在今天恰恰应该被宣扬。或许借助现代主义大师康定斯基和美国抽象表现主义艺术家波洛克的创作,有助于我们进入对乱书的欣赏。从根本上讲,王冬龄和上述两位艺术家一样,都是在突破既有艺术规范的基础上,强调自我精神的表现和创造性的发挥。他们的作品都向观者敞开了想象和阐释的自由空间。从形式角度来看,无论是波洛克的泼洒、康定斯基的点线,还是王冬龄的乱书,都强调线条的律动、空间的结构和作品的表现力。只是因为文化基因、艺术根脉及创作媒介的差异,他们的表现又各有特点。波洛克的作品强调笔触的随意性和线条的流动感,康定斯基则着重展现线条本身的音乐性和韵律美,王冬龄的书法则讲究笔势的奔放和笔意的贯通。

乱书的诞生既显示出王冬龄根植传统的基础,也彰显了他勇于创新的胆气。这种从不故步自封、自我设限的前进姿态贯穿了他的整个书法创作生涯。单以媒介而论,王冬龄不但尝试过在各种不同的纸张(各类宣纸、水彩纸、报纸、相纸、油性纸等)上进行书写,还在竹子、木头、玻璃、亚克力、布料、陶瓷、墙壁等介质上书写。由于媒介的特性不同,他所使用的书写材料也各不相同,除传统的墨以外,银盐、漆、油性物质等都是他的特殊“墨水”。此外,他还将书法与其他当代艺术形式相融合,将书写与装置、影像、观念、行为等相关联,远远超越了传统书法的审美范畴,大大拓宽了书法艺术在当代环境中的可能性。让笔者最为感动的作品就是《竹径》,该作品将书法、历史与自然生态完美地结合在了一起。书法不在别处,而在此处。观者可步入其中,入境即感怀。

二、从书斋突围

如果说乱书代表了王冬龄植根传统的当代跃进,那么大字书法则是他书法社会学的重要实践路径。1987年,他在中国美术馆的个展上首次展出大字书法《泰山成砥砺,黄河为裳带》,其中仅一个“带”字就有三米多高,极具震撼效果。沙孟海先生看后也不禁感叹“真伟观也”。进入新世纪,王冬龄在杭州先后完成了巨幅草书《逍遥游》《老子》《心经》等作品,并于2013年与《钱江晚报》合作开启“大字走世界”项目。从香港到纽约,从西安到巴黎,王冬龄在世界多个城市的各类场地进行大字书写,以社会性话题引发人们对书法的关注和热议。2015年,王冬龄为杭州的苹果旗舰店外墙题写了苏轼的《饮湖上初晴后雨》巨幅书法。墨笔书写的大字与鲜红的苹果LOGO跨界组合,别有一番意趣。同年,他还在自己的工作室会见了苹果CEO库克,教他写中国书法,一时成为网络热点。前段时间,华为推出了与中国美术学院联合开发的最新绘画应用软件,内置了一百多种预制笔刷,受到众多绘画爱好者的追捧。由此联想到早在大约十年前,作为中国美院教授的王冬龄就曾在iPad上写书法。近年来,他还利用AR技术进行书写,不禁让人感叹这位年近八旬老人的新潮与前卫。种种跨界、出圈的行为给王冬龄带来了不少争议,但也的的确确让书法和当下社会以前所未有的方式联系在一起。他让这门古老的艺术从阳春白雪的书斋案头走向街头、走向日常,走到了时代的最前沿。

有人说王冬龄喜欢当众创作,表演成分过多,不是严肃的书写。事实上,书法创作,特别是行草书创作的快速性,使其自古以来便成为一种可供观赏的艺术形式。唐朝文宗时期,曾颁布诏书御封李白的诗歌、张旭的草书、裴旻的剑舞为大唐“三绝”。将诗歌、书法与剑舞并论,本身就说明前两者亦有观赏之价值。唐人李肇《国史补》记,“(张旭)性嗜酒,每大醉,呼叫狂走,乃下笔,或以头濡墨而书”。对于求字者而言,此时欣赏的不仅是书法作品,更是一场书写行为的表演。从王羲之雅集后醉书《兰亭序》,到苏轼游庐山作《题西林壁》,书写的观赏性本就是题中之义。现场书写可以视为一种即兴创作,它要求书法家在短时间内完成作品,这对书写者的功力是一种考验。当众书写时,书法家的心境、情绪都会直接影响作品的风格和气质,虽然难度更大,但也常因特别的状态而诞生佳作。王冬龄的现场书写,正是对这一传统的继承和发展。更何况在北京太庙的那次寒风中的书写,笔者亲见王老师以水当墨就地创作,其行为当然可以让人联想到清晨在各大公园地上练字的老者。但对于这样的一位书法家,这样的写过即逝的作品,平添了更具哲思的意味。

当然,我们也可视为王冬龄的创作行为是一种“具身性”的呈现。学者德莫特·莫兰(Dermot Moran)教授认为:“身体”作为从内在被经验到的身体,是对具身意识的经验。就此而言,身体意味着一个有灵的、活生生的器官——也即以确定之主体性的、第一人称的方式被经验到的身体。他还指出:经过胡塞尔与梅洛-庞蒂的研究,身体才在哲学史上第一次作为真正的核心议题而出现。梅洛-庞蒂甚至认为视觉与触觉一样,也具有一种“自反性”——它使得看者与被看者处于一种相互交换的关系之中。就此而言,梅洛-庞蒂深化了胡塞尔对触觉之“自反性”的阐述,使之成为所有身体“器官”或者所有感知模态的一般的本体论特征。笔者不是这方面的专家,但对“具身性”的研究,主体与客体的关系在人工智能时代有着尤为重要的价值。因此,王冬龄的艺术实践不仅在突围,也在成为被研究的对象。

还不仅如此,当人们对拼音输入、敲击键盘的依赖超过执笔手写时,对公众尤其是年轻人而言,人与书写的关系已然渐行渐远。在这样的背景下,王冬龄当众挥毫泼墨,将书法创作的全过程毫无保留地展现在观众面前,无疑是在消除大众与书法之间的隔膜。观者可以直观地看到艺术家挥毫时的身体动作、呼吸节奏,感受笔锋在宣纸上游走时的酣畅、顿挫、加速、停顿,甚至捕捉墨色在纸面上晕开、渗透的微妙瞬间。这种身临其境的体验,对于书法的推广和普及无疑具有很好的效果。

三、从本土突围

王冬龄书法成就的获得,既得益于自己的不懈探索,也离不开外界因素的启发和刺激。其中,来自国外的影响是不可忽视的重要部分。美国历史学家费正清曾提出极具影响力的“冲击—回应”模式,即认为中国现代社会的发展是受到西方冲击后做出的被动反应。这一观点在今天被认为是“西方中心主义”的表现,并不完全符合历史事实。但不可否认的是,近代以来,来自西方社会的冲击,对中国而言,既是一种压迫,也是一种动力。中国的现代艺术也正是在这样的环境中发展起来的。

20世纪80年代初期,王冬龄从浙江美术学院毕业后留校任教,很重要的一项工作就是教授留学生书法。他在教学过程中发现,西方学生对书法本身的了解甚微,但往往具有综合的西方文化艺术素养。他以因材施教的方式对学生进行授课,在此过程中还能教学相长,对自己的创作产生启发。1989年,王冬龄赴美国讲学,教授中国书法。四年间,他完全沉浸在美国的社会文化中,深受西方当代艺术、现代舞蹈等启发,认识到中国书法在当代发展的意义和方向。无论是后来的大字、乱书,还是将书法与其他艺术相结合的跨界实验,都与他的国际视野密不可分。德国接受美学家沃尔夫冈·伊瑟尔(Wolfgang Iser)提出,艺术家在创作前要设定自己“隐含的读者”。对于王冬龄而言,他对书法艺术的受众的预设绝不仅仅局限于国内,而是面向全世界的观众。

事实上,早在20世纪上半叶,徐悲鸿、刘海粟等前辈名家前往欧洲、东南亚举办中国艺术展时,都会现场进行国画创作,以便让其他国家的观众更直观地了解中国画的创作过程,近距离感受笔墨韵味。时至今日,即便全球化的发展已让不同的国家、种族产生紧密联系,但在西方世界眼中,中国书法似乎仍然蒙着一层充满东方神秘色彩的面纱。多年来,王冬龄抱持着让书法走向世界的理想,在欧美许多国家举办展览,作品也被世界各大博物馆收藏。他经常在展览现场进行即兴书写,将人体与书法、运动与创作相结合。这种“表演性”的创作,在很大程度上契合了西方观众对艺术家的认知,极易引起他们的兴趣和共鸣。这种即兴挥毫在笔墨韵律、动势节奏上呈现出与抽象表现主义绘画相似的特质,能唤起西方观众的某些审美经验,进而拉近他们与书法之间的距离。王冬龄曾回忆自己在布鲁克林国家美术馆、比利时皇家美术馆等地进行大字书写时,让现场观众受到了极大震撼。这种将书法创作过程“现场化”“透明化”的方式,无疑能让外国观众直观地感受到中国书法的魅力,最大限度地消除文化的隔阂,对于书法艺术走向世界具有直接意义。

早在20世纪50年代,井上有一等日本书法家的作品就开始在国际上亮相,作为现代书法的代表在世界范围内产生影响,也在很大程度上主导了西方世界对于书法的认识。时至今日,以王冬龄为代表的中国当代书法家的创作实践逐渐获得国际认可,我们既可以说这是一种话语权的争夺,也可以说这是当代书法多样性的另一种表现。总之,我们欣喜地看到,王冬龄一直以来让书法走向世界的理想正在逐渐成为现实。

结语

在量子物理学中,粒子和波的性质不能简单地划分为独立的类别,一个量子实体可以同时表现出粒子和波的特性,这也是王冬龄的艺术特征。更何况他喜欢穿红色,那红色的袜子踩在白纸上,成为巨大墨线中的亮色。当代社会十分流行一种观点:没有争议的人往往是平庸的。齐白石说“不喜平庸”,这才是艺术家。回顾王冬龄六十多年的书法创作、艺术探索的生涯,既显示出中国书法千年文脉的传承有绪,也彰显出书法的基因价值和其在当代环境中的生命力和可能性。王冬龄的实践总体上看是解放自己,如骑在一匹脱缰的野马之上,在他自我建构的旷野上驰骋。然而,他没有脱轨,没有脱离艺术之于世界的价值核心。尽管他的创作路径和风格充满争议,但只要不愿看到书法乃至艺术成为风干的历史标本,那么以王冬龄为代表的艺术家的各种努力和尝试就值得被肯定。“突围”比“困死”更需要勇气,也更值得钦佩。

(文/吴洪亮)

Not One, Nor Two:

Wang Dongling's Breakthroughs

In the Palace Museum in Beijing, there is a famous portrait of Emperor Qianlong One or Two (《乾隆皇帝是一是二图》).In the picture,Emperor Qianlong sits on a couch in Chinese clothing, and a portrait of him hangs on the screen behind him. This form is not new, but Qianlong had his own thinking. He wrote in the inscription: "It is one and it is two. They are similar but also separate. Confucianism or Mohism (a form of utilitarianism developed by Mozi in China around 300 BC.), what should one consider and think?" It is generally interpreted as Qianlong's attempt to show that he was amenable to the doctrines of both Confucianism and Mohism, reflecting the notion that seeking harmony is the superior choice. But I'm afraid contemporary art is often the opposite. When asked to write something for Wang Dongling's new book, I thought of a phrase referring to this painting: "not one, nor two." I believe it is more appropriate for the description of Wang's breakthroughs and bold practice in calligraphy.

His art is not defined by “what it is,” but by the experiments he conducts to show “what it is not.” The expression “Not one, nor two” represents the emancipation from the limitation of “one” and “two,” aiming to transcend simple dichotomous thinking. It points to a more complex, comprehensive, and open understanding, emphasizing the value of non-absoluteness. It is about change and development, highlighting that the practice of art cannot be quantified or simply defined. Wang Dongling is such a practitioner. At nearly eighty years old, his pioneering explorations remain steadfast, often prompting the questions: Are his works still calligraphy? If they are, where lies the core and extension of calligraphy? Additionally, Wang has enjoyed live performances and has done so all over the world. Does this undermine the seriousness of the art of calligraphy?

To answer these questions, we need to briefly look at Wang Dongling’s journey. According to his self- described experiences, it can be divided into three phases: The first phase was from 1962 to 1979, during which he consolidated his calligraphy foundation by studying various styles; the second phase was from 1979 to 2007, when he specialized in Cursive Script, pioneering large-format calligraphy and exploring the modern development of calligraphy; the third phase, starting from 2008, has seen him experimenting with various materials on different mediums, placing calligraphy in the context of contemporary art and creating the unique Entangled Script. Throughout his career pning over 60 years, Wang Dongling has experienced many ups and downs: the early days of new China, the decade of turmoil, the transition from a planned economy to a market economy, and the development from the information age to the intelligence age. In the tide of the times, some people choose to remain unchanged and only mind their own affairs, while others choose to lead the trend and ride the tide. Wang Dongling undoubtedly belongs to the latter. To examine his creative journey, we should not only pay attention to the creation of his ontological language, but also consider the concept of “what is not” in a broader sense. With this in mind, we can view Wang Dongling's artistic practice from three perspectives.

1. Break out of the tradition

In the Tao of Writing exhibition in 2012, Wang Dongling’s The Moon over the River on a Spring Night (《春江花月夜》) marked the debut of his Entangled Script. Since then, this extremely difficult-to-read style of calligraphy has been a subject of much controversy. In fact, Entangled Script is only a result. To truly understand its significance, it is necessary to trace back and sort out the logic of its development.

There is no doubt that Wang Dongling is gifted in calligraphy. In 1962, at the age of 16, he participated in the Second Calligraphy Seal Exhibition of Jiangsu Province with a piece of work in Small Seal Script, becoming the youngest participant. His works were displayed in the same hall as established masters such as Lin Sanzhi ( 林散之 ), Gao Ershi ( 高二适 ), and Hu Xiaoshi ( 胡小石 ). It became a topic of time. In addition to his innate talent, his fortunate encounters also played a significant role. In 1967, he was introduced to Lin Sanzhi through Wei Tianchi ( 尉天池 ) and became Mr. Lin’s student, laying the foundation for him to acquire the true essence of Great Cursive Script. In 1979, the first postgraduate course in calligraphy was admitted by the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art). He was admitted and became a student of Lu Weizhao ( 陆维钊 ), Sha Menghai ( 沙孟海 ), and Zhu Lesan ( 诸乐三 ). He was greatly influenced by Sha Menghai's powerful large calligraphy works, which laid the groundwork for his future practice with large brushes.

His early experiences in learning calligraphy laid a solid foundation for his future works, and it is in this vein that Entangled Script developed. In his own words, the “chaos” of Entangled Script is “actually breaking the iron law of traditional calligraphy that characters cannot overlap; now not only can lines cross, but also words can overlap each other.” (Wang Dongling, Autobiographical Notes on Learning Calligraphy) Wang Dongling compared the calligraphy of Dong Qichang ( 董其昌) and Xu Wei ( 徐渭) to reveal the logic behind his Entangled Script. While Dong's calligraphy emphasizes the rules of layout, with clear spacing between lines that presents a sense of nobility and dignity, Xu Wei's approach intentionally breaks the “flow of lines,” weakening the notion of regularities. Wang Dongling took this a step further by breaking the left-right division and allowing lines and characters to overlap, completely defying traditional calligraphy layout norms. The birth of Entangled Script was also influenced by a natural phenomenon. It is said that Huai Su's great success in cursive writing during the Tang Dynasty was inspired by the surging clouds of summer, while Wang Dongling's Entangled Script was inspired by the withered lotuses in West Lake during winter. The China Academy of Art, located by West Lake, provided him with the opportunity to form a long-term bond with the lotuses. His favorite is the withered lotuses in wintertime. Wang Dongling was deeply moved by their withered appearance and the regenerative force within them. Over the past decades, he has photographed thousands of withered lotuses, and this kind of lotus watching has subtly infiltrated his calligraphy. When some audience members saw Wang Dongling's massive Entangled Script representation of The Thousand Character Classic (《千字文》), they were naturally reminded of the withered lotuses in West Lake. From calligraphy tradition to natural reflection, the inevitability and serendipity of Entangled Script is both logical and full of providence.

Entangled Script was born with both a self-evident logic of development and a distinct awareness. People are increasingly aware that the environment in which Chinese calligraphy, with its millennia- long history, has developed, has changed profoundly. Brushes, ink, paper, and ink stones are no longer necessary tools for writing. Calligraphy has transitioned from a daily routine to an art form, and from a part-time job to a profession. Calligraphy occupies a special category in today's classification of art and is even inscribed on the World Intangible Cultural Heritage List. Wang Dongling realized early on that merely following the old path of traditional calligraphy is no longer suitable for the present day. The challenge we face today is not only how to pass on the tradition but also how to revitalize calligraphy in the contemporary environment and develop it further. The contemporary transformation of calligraphy, and even “planting bamboo in the age of 5G,” are endeavors many contemporary artists, including Wang Dongling, are undertaking. Wang Dongling regards calligraphy as the root of ink art and seeks to link the majesty of Wild Cursive Script with abstract ink. This forms the theoretical basis and contemporary characteristics of Entangled Script. As the difficulty of recognizing text increases dramatically, its practical function is subsequently weakened, bringing the shape, line, and layout of the writing itself to the forefront. At this point, calligraphy transforms into a form that transcends traditional aesthetics and evolves into a form of abstract art. Two thousand years ago, Zhao Yi's ( 赵壹 ) critique of cursive writing beyond its practical function in Non-Cursive Script (《非草书》 ) should be rejected today. Perhaps the modernist master Kandinsky and the American Abstract Expressionist artist Pollock can help us appreciate Entangled Script. Fundamentally, Wang Dongling, like Kandinsky and Pollock, emphasizes the expression of individual spirit and creative play by breaking established norms. All their works open up free space of imagination and interpretation for viewers. Whether it is Pollock's splashes, Kandinsky's dots and lines, or Wang Dongling's Entangled Script, each form emphasizes the rhythmic movement of lines, the structure of space, and the expressive power of works. It is only due to differences in cultural genes, artistic roots, and mediums that each exhibits their individuality. Pollock's works emphasize the randomness of brush strokes and flow, Kandinsky focuses on musicality and rhythmic beauty, and Wang Dongling's calligraphy is concerned with the exuberance of brush strokes and coherence.

Entangled Script shows both Wang Dongling's deep roots in tradition and his boldness to create. This forward-looking approach has been present throughout his entire career. In terms of media alone, Wang Dongling has not only experimented with various kinds of paper (rice paper, watercolor paper, newspaper, photo paper, wax paper, etc.), but also bamboo, wood, glass, acrylic boards, fabric, ceramics, and walls. Due to the different nature of each medium, he uses various materials to write with, including traditional ink, silver salt, lacquer, and oil-based pigments. These are his special “inks.” Furthermore, he integrates calligraphy with other contemporary art forms, correlating it with installation art, video, conceptual art, performance, and more. He goes far beyond the scope of traditional calligraphy, greatly broadening its possibilities in contemporary settings. For this writer, the most touching work is Bamboo Trail (《竹径》), which is a perfect combination of calligraphy, history, and ecology. Here, calligraphy is not a distant art form, but a living experience, inviting the viewer to wander in and become immersed.

2. Break out of the studio

If Entangled Script represents Wang Dongling's contemporary leap forward, then monumental-sized calligraphy is an important path for his sociology of calligraphy. In 1987, Mount Tai has become a pillar of strength and the Yellow River a belt of garments (《泰山成砥砺,黄河为裳带》) debuted in his solo exhibition at the National Art Museum of China. The character “带 ” alone stands more than three meters high and makes a powerful impact. Sha Menghai could not help but exclaim in surprise: "This is a really great view." Entering the new century, Wang Dongling has completed large cursive works in Hangzhou, such as A Happy Excursion (《逍遥游》), Laozi (《老子》), and Heart Sutra (《心经》). In 2013, he initiated the Big Writing Going Around the World Project together with Qianjiang Evening News. From Hong Kong to New York, to Xi'an, and to Paris, Wang Dongling has been creating large- sized works in various venues around the world, sparking social discussions about calligraphy. In 2015, Wang Dongling created a large-sized work of Su Shi's ( 苏轼 ) verse, Drinking on the Lake after the First Clearing Rain (《饮湖上初晴后雨》), for the exterior wall of Apple's Hangzhou flagship shop. The huge black characters and the bright red Apple logo created a unique combination. In the same year, he also became an internet sensation when he met Apple CEO Tim Cook in his studio and taught him Chinese calligraphy. Not long ago, Huawei launched its latest painting application, jointly developed with the China Academy of Art. With more than 100 pre-made brush settings built-in, it is sought after by many painting enthusiasts. This is reminiscent of the fact that nearly a decade ago, Wang Dongling, a professor at the China Academy of Art, used to write calligraphy on his iPad. In recent years, he has also experimented with AR technology. One can't help but marvel at how hip and avant-garde he is. All kinds of crossover activities have brought Wang Dongling a lot of controversy, but they also connect calligraphy with the contemporary world as never before. He has brought this ancient art from the studio to the streets, to everyday life, and to the forefront of the times.

Some say Wang Dongling's preference for public performance is too showy and not serious. As a matter of fact, the rapidity of calligraphy, especially in cursive writing, has made it an art form to be viewed since ancient times. During the reign of Emperor Wenzong of the Tang Dynasty, an imperial edict named Li Bai's ( 李白) poems, Zhang Xu's ( 张旭) cursive script, and Pei Min's ( 裴旻) sword dance as the “Three Greats” of the Tang Dynasty. The juxtaposition of these three art forms indicates that the first two can also offer amusement. Tang Dynasty historian Li Zhao ( 李肇 ) wrote in Supplement to the Tang History (《国史补》): “(Zhang Xu is) an alcoholic. Every time he got drunk, he would make loud noises and walk around, then pick up the brush and write. Sometimes he would even dip his head in ink to write.” For those who admire calligraphy, what is appreciated here is not only the writing on paper but also the performance of the act of writing. Wang Xizhi ( 王羲之 ) wrote the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion (《兰亭序》) after getting drunk at an elegant gathering. Su Shi traveled to Mount Lushan and wrote Written on the Wall at West Forest Temple. The amusement nature of calligraphy is part of what it’s all about. On-the-spot writing can be regarded as a form of improvisation, requiring the calligrapher to complete the work within a short period of time. It is a test of the calligrapher's ability. In public writing, the calligrapher's state of mind and emotions directly affect the work. Although it is more difficult, masterpieces are often born on these special occasions. Wang Dongling's live performance is a continuation and development of this tradition. I witnessed his impressive writing in the cold wind at the Imperial Ancestral Temple in Beijing. Wang used water as ink to write on the ground. This act can, of course, be associated with the scene of elders practicing calligraphy in parks early in the morning, a common sight in China. On the ground to practice calligraphy, the old man, such a great calligrapher, creates works that are transient, adding a more philosophical meaning. His writing about the impermanence of life adds a layer of philosophical depth.

Of course, we can also see Wang Dongling's creative behavior as a kind of 'embodied' presentation. According to Dermot Moran, "the body" as embodied consciousness is experienced from within. In this context, the body means a spiritual, living organ—that is, a body experienced in determinate subjectivity, in the first person. He also pointed out that it was with the studies of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty that the body emerged for the first time in the history of philosophy as a central topic. Merleau- Ponty even argued that vision, like touch, has a" reflexivity" it puts the viewer and the viewer in an interchangeable relationship. In this respect, Merleau-Ponty deepened Husserl's account of the "reflexivity" of touch as a general ontological characteristic of all bodily "organs" or of all perceptual modalities. This author is not an expert in this field, but the study of "embodiment" and the relationship between the subject and the object are particularly important in the age of artificial intelligence. As a result, Wang Dongling's artistic practice is not only breaking free out the studio but also becoming an object of study.

Not only that, when people rely more on keyboards than handwriting, the relationship between people and calligraphy has already drifted away for the general public, especially for younger generations. In such an environment, Wang Dongling's public brush-waving and ink-splashing, showing the whole process of calligraphy to the audience without any reservation, is undoubtedly bridging the divide between the public and the art form. The viewer can see the artist's body movements and breathing rhythms in situ, experience the wielding of the brush, and feel the rhythm of the brush: the soundness, the staccato, the acceleration, and the pause. As the brush wanders across the rice paper, one can even capture the subtle moments when the ink color bleeds and penetrates the paper. This immersive experience is undoubtedly effective for the promotion of the art of calligraphy.

3. Break out of the country

The achievements of Wang Dongling are not only due to his own unremitting exploration, but also the inspiration and stimulation of external factors. The influence from abroad is an important part of this and cannot be ignored. The American historian John King Fairbank coined the influential “shock- response” model, in which he argued that the development of modern Chinese society was a passive response to the impact of the West. This view is today considered a manifestation of Western-centrism and is not entirely consistent with historical facts. However, it is undeniable that since modern times, the impact of the West has been both an oppression and an impetus for China. It is in this environment that modern art in China has developed.

In the early 1980s, after graduating from the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, Wang Dongling stayed on as a teacher, and one of his important jobs was to teach calligraphy to international students. In his teaching, he found that Western students knew little about calligraphy but often had comprehensive knowledge of Western culture and art. He taught his students in a way that was tailored to their needs, and in the process, it also inspired his own creativity. In 1989, Wang Dongling traveled to the United States to teach Chinese calligraphy. During the four years, he was completely immersed in American culture and was deeply inspired by Western contemporary art and modern dance. He recognized the potentials and directions of the contemporary development of Chinese calligraphy. Whether his large and Entangled Script or his crossover experiments in combining calligraphy with other arts, they are all inextricably linked to his international outlook. German scholar Wolfgang Iser, who promoted the concept of reception-aesthetic, suggested that the artist should set the “hypothetical viewers” before working on a piece. For Wang Dongling, his preconceived viewers for his calligraphy are by no means limited to the domestic community but are aimed at the worldwide stage.

As a matter of fact, as early as in the first half of the 20th century, when artists from the previous generation, for example, Xu Beihong ( 徐悲鸿 ) and Liu Haisu ( 刘海粟 ), traveled to Europe and Southeast Asia to hold exhibitions, they would create Chinese paintings on the spot in order to let the audience have a more intuitive understanding of the creation of Chinese painting and to feel the charms of ink and brushwork up close. Today, even though globalization has brought different countries and cultures into close contact, in the eyes of the West, Chinese calligraphy still seems to be covered with a veil full of oriental mystery. Over the years, Wang Dongling has held the ideal of bringing calligraphy to the world, holding exhibitions in Europe and the United States, and his works have been collected by major museums around the world. He often performs writing at exhibition openings, showing the audience the unifying of the human body with calligraphy movement in writing. This kind of performative work is very much in line with the Western audience's perception of the artist, and it is very easy to resonate with them. This kind of improvisation presents qualities similar to Abstract Expressionist paintings, in terms of rhythms and dynamics, hence evoking certain aesthetic experience in Western audience, and thus bringing them closer to calligraphy. He once recalled the great impact he made on the audience when he created huge works at the Brooklyn Museum and

the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Belgium. This kind of “on-site” and “transparent” process will undoubtedly allow foreign audience to intuitively feel the charm of Chinese calligraphy, eliminating cultural barriers. It is of direct significance for introducing the art of Chinese calligraphy to the world. As early as the 1950s, Japanese calligraphers such as Inoue Yuichi began to make their international impact, and they were seen as representatives of modern calligraphy, largely dominating the Western world's perception of calligraphy. To this day, the practice of contemporary Chinese calligraphers, represented by Wang Dongling, have gradually gained international recognition. We can say it is both a fight for voice in the international community and a manifestation of the diversity of contemporary calligraphy. We are pleased to see that Wang Dongling's longstanding ideal of bringing calligraphy to the world is gradually becoming a reality.

Concluding remarks

In quantum physics, particles and waves cannot simply be divided into separate categories, as a quantum entity can exhibit the properties of both. This is also what characterizes Wang Dongling's art. What's more, he likes to wear red, and those red socks on white paper become bright sparkles among huge ink lines. There is a very popular view in contemporary society: people who are not controversial tend to be mediocre. Qi Baishi ( 齐白石 ) said: “I don't like mediocrity,” and that's what makes an artist. A review of Wang Dongling's career, over 60 years of artistic exploration, shows both the continuation of the millennia-old cultural lineage of Chinese calligraphy and the vitality and possibilities of the genetic value of it in the contemporary environment. Wang Dongling's practice seem to be the liberation of himself, like riding a wild horse, galloping in the wilderness of his self-construction. However, he is not derailed from the core value of art. Despite the controversy over his creative path and style, as long as one does not want to see calligraphy or even art become a dry historical specimen, the various efforts and attempts made by artists, represented by Wang Dongling, deserve to be recognized.

Breaking out takes more courage and is more admirable than being trapped.

Wu Hongliang

(来源:巽汇、天津市文化和旅游局)

作者简介

吴洪亮,全国政协委员、北京画院院长、中国美协理事、中国美协策展委员会副主任兼秘书长、北京美协副主席。

吴洪亮是一位具有影响力的策展人,长期致力于齐白石、20世纪美术史的研究。在他主持下,北京画院美术馆入选首批9家国家级重点美术馆。他参与策划并将齐白石的艺术带到匈牙利、日本、列支敦士登、希腊等国家及中国澳门等地区展出。参与组织了“策展在中国”论坛、齐白石艺术国际论坛等学术项目。2008年参与北京奥运会开闭幕式及公共艺术项目。2019年担任威尼斯双年展中国国家馆策展人。担任2022年北京冬奥会和冬残奥会公共艺术全球征集项目的策划委员会主任。近年来,有数十篇论文发表在《文艺研究》《美术》《美术观察》《美术研究》等专业刊物,出版专著《一叶知秋》等。

艺术家简介

王冬龄,当代著名书法艺术家,现为中国美术学院现代书法研究中心主任、教授、博士生导师,兰亭书法社社长。江苏省南通市如东县人,出生于1945年,1981年从浙江美术学院(今中国美术学院)首届书法研究班毕业,获硕士学位,留校任教。1989年赴美国明尼苏达大学讲授中国书法。1994年回中国美术学院执教。编著有《王冬龄书法艺术》《王冬龄创作手记》《王冬龄谈现代书法》《林散之》《王冬龄书画集》等多种著作。