As the highest value in Jing Hao’s theory of painting, truth has an inward moral and spiritual orientation, and is the way to access Qi and Yun, so that, by acquiring the truth, people can generate Qi and Yun, and things can generate Qi and Matter. Aiming at truth is not only to get the Qi of heaven and earth, but also to reach the harmony of man and heaven and earth; through the personal charm of the painter, Qi is generated. In the special essay Qi-Yun is Unavailable from Being Taught (Insights into Painting), Guo Ruoxu in the Northern Song Dynasty says, “Looking at the talents since ancient times, I find that many of them are high-ranking officials or reclusive Confucian scholars. They wander all over the world of art in their kindness, exploring the profound and subtle knowledge, and their perfect good tastes completely reflect in their paintings. Given their character, Qi-Yun in their paintings cannot be low; and given the strong Qi-Yun, the livingness has to come in. All paintings must have a good sense of Qi-Yun before they can be called treasures”. Here, the world of morality and the world of heavenly principles are connected to each other, and Qi-Yun is the representation of personal morality and spiritual cultivation in painting, which can only be realized through self-awareness and practice, and is the display of the artist’s disposition that is constantly being polished. After returning to a thorough understanding of one’s authenticity, one can acquire the “truth” by removing complex concepts and the inertia of inherent thinking with no falsehoods, and by connecting one’s free self to the world of heavenly principles which is the essence of all things.

II. “Brush and Ink” and “Four Potentials”

Brush and ink are two essentials in Brushwork Notes, and the in-depth excavation, inheritance and development of the brush-ink system is also an important achievement that Lin Haizhong has explored in his paintings over the years. “The brushwork, although following rules, operates flexibly, without matter or form. Ink is a type of painting that shades in representing things, seemingly unrelated to brush”. Moreover, four potentials are further normalized: “there are four potentials in all brushes, which are called sinew, flesh, bone, and breath. That brush ceases but not broken is called sinew. That undulation into a real is called flesh. That life and death are represented rigidly is called bone. That traces of painting are not tarnished is called breath. So, I know that ink outdoing matter loses its body; the vanishing looks spoil normal breath, and the stiff sinews have no flesh; the broken traces have no sinew, and the obsequious has no bone”.

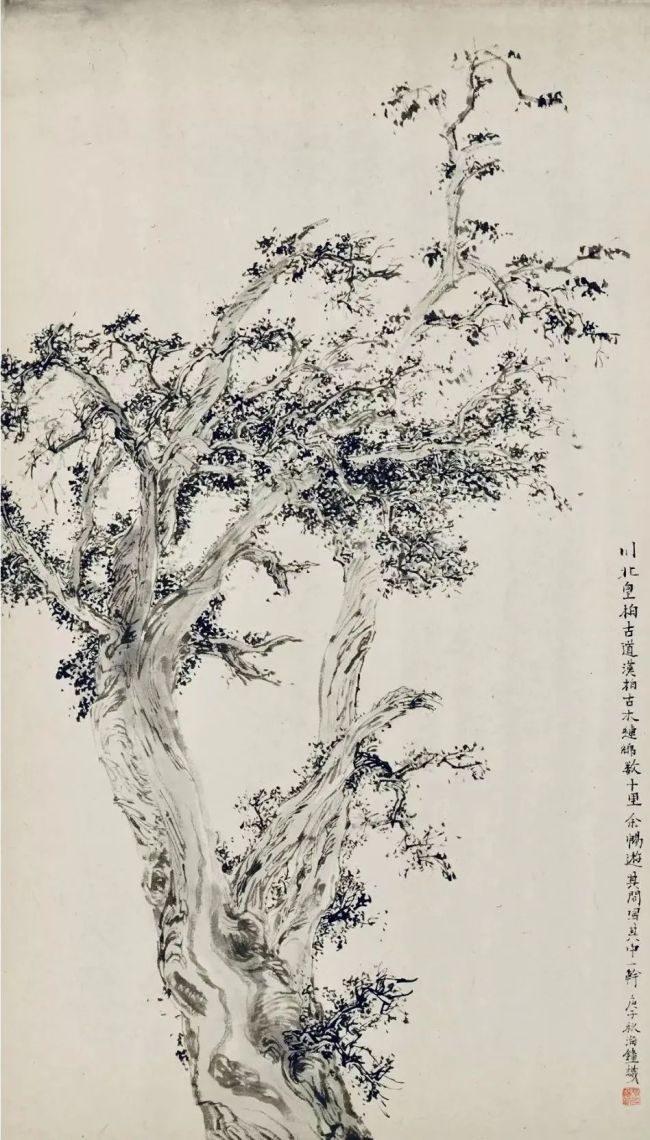

皇柏古道纸本水墨 Ink on paper37x64cm2020

Why has “brush-ink” become an inherent attribute of Chinese painting? And why has it constantly become the focus of discussion in the modern transformation of Chinese painting? In the end, the material property of “water-ink” can only be used to replace the title of Chinese painting with “brush-ink” as its core. Is Picasso’s painting with brush and Xuan paper wash painting? Is Wang Dongling’s writing with acrylic materials not calligraphy? The term “brush-ink” is related to the self-construction, self-training and conscious maturity of Chinese art. Brush and ink is a form of life. In the Han Dynasty and the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, calligraphy first completed its artistic self-awareness and established its own language system. During the Han Dynasty, the cursive script of Chinese calligraphy was detached from its utilitarian function, and Zhang Zhi, the sage of cursive script, made calligraphy an expression of the writer’s personality. The real comprehensive self-consciousness was the emergence of running script, regular script and present cursive script, i.e., “present style”. Wang Xizhi’s rich and varied calligraphy system with aesthetic ideals became the representative of the self-consciousness of calligraphy, and also became the foundation for the development of the later generations. Cui Yuan’s Cursive Script’s Potential in the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty, Cai Yong’s Seal Script’s Potential and Brush Fugue in the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty, and Zhao Yi’s Non-Cursive Calligraphy put forward the important concept of potential, from which the four potentials in Brushwork Notes inherited. The most important concept in the calligraphy of the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties is “brushwork”. The matter of brushwork itself and its abstract combinations generate the “handwriting”, such as “proficient handwriting”, “fluent handwriting”, “outstanding handwriting”, “the handwriting is too poor to measure”, and “being famous only for his handwriting” and so on. There are also combinations of brushwork and power, such as “the power of the brushwork is amazing”, “its power outdoing Wang Zijing’s”, “extremely powerful brushwork”. There is a summary of brushwork: “lightly brushing and slowly wiping, relaxedly pressing and sharply poking, drawing horizontally and leading longitudinally, pulling leftward and winding rightward” (Cheng Gongsui, who lived in the Western Jin Dynasty). In In Praise of the Mood of Brushwork written by Wang Shengqi of the Southern Dynasty, specific requirements of brushwork were described as follows: “Bone and flesh should be plentiful and tender, getting into the spirit. Vertical strokes should be like a lance, and horizontal ones a nail. Stretching out should be like the phoenix spreading the wings, and standing out should be like Lingzhi standing upright. Thick strokes are not pressed heavily, and thin ones are not wiped gently. Strokes run back and forth, even if the slightest ones are related to the quality of characters”. Calligraphy theories in the Northern and Southern Dynasties include many important concepts: stroke, rule, bone, potential, nature, and work. Sinew is the highest, followed by bone, and the last one is flesh, the object of criticism. “Scripts superior in sinew are reserved, which need difficult skills, higher in quality. Scripts superior in bone, represented in their shapes, are inferior; and scripts full of flesh are the worst ones”. “Scripts that have much strength and abundant sinews are lofty, and those that have no strength and no sinew are flawed”. (Liu Tao, Chinese Calligraphy History of the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties) Painting theory works are also stabilized: Zong Bing’s Of Painting Shanshui, Wang Wei’s On Painting, Xie He’s Ancient Paintings, and many others, laid down the theoretical system of Chinese painting. The requirements for the brushwork are “to imitate the body of emptiness in one brushstroke”, “the bone method of using the brush”, and “the novelty of the brushwork” ... By the Tang Dynasty, Zhang Yanyuan’s On the Brushwork Deployed by Gu, Lu, Zhang and Wu (Records of Famous Paintings of All Ages) made clear the origin of “one brushstroke”: “in the past, Zhang Zhi learnt from Cui Yuan and Du Du’s methods of cursive script, and thus changed it to become the present cursive script. The posture of the script is formed by one stroke, and Qi flows through the connection, without breaking in neighboring lines. It was only Wang Zijing who grasps its deep purpose, so the character at the beginning of the line often follows its predecessor – that is called the script in one stroke. Later, Lu Tanwei also practiced painting in one stroke. Therefore, it is known that calligraphy and painting use the same method. Zhang Sengyou’s pointing, dragging, chopping,and wiping, following the instructions of Mrs. Wei’s On the Potentials of Stroke,are differently ingenious. It is also known that calligraphy and painting use the same brushwork. Wu Daoxuan was unique both in ancient and present times, without seeing Gu and Lu or anyone coming from behind. He taught Zhang Xu in penmanship, which also revealed that calligraphy and painting use the same brushwork. Since Zhang was known as “the wizard of calligraphy”, while Wu “the saint of painting”, miracles in their works came from nature, and the spirit was endless.”.

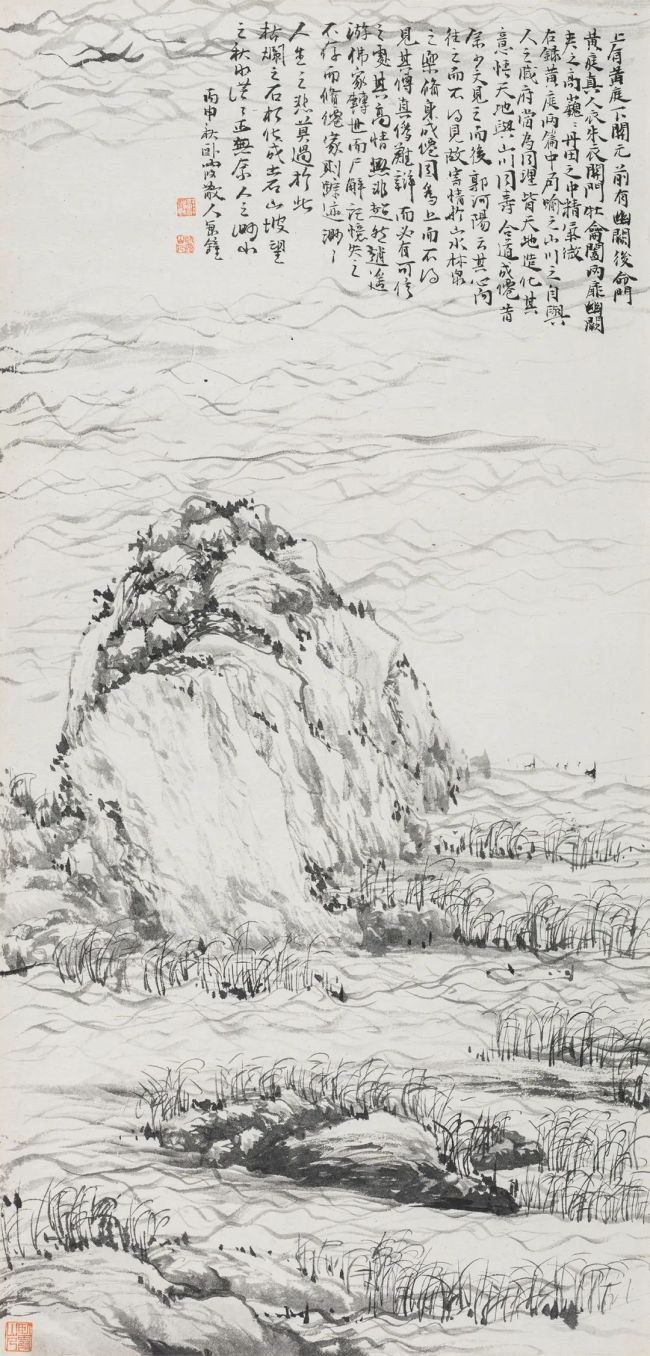

遥山动波图纸本水墨 Ink on paper67x33cm2016

By tracing back, we can see that the requirements of brushwork as mentioned in Brushwork Notes: “without matter or form, like flying and moving” is the pursuit of independent aesthetics of the brushwork. That “Using the brush in bone method” refers to power, and that “one stroke” refers to sinew. In saying that “the brushwork, although following rules, operates flexibly”, rules are ones that the brushwork follows, and “flexibility” is that in what Huang Binhong called “smooth, controllable, elastic, powerful, and flexible”. This is also the characteristics of Lin Haizhong’s brushwork: “all points and strokes are out of surprise”, and the postures of brushwork and combinations are billowing, beautiful and powerful. After more than thirty years of refinement, he has formed his own unique and perfect brush-ink structure.

The brushwork is not so much a technical system as it is a way to control the physical and mental experience of time, a way of self-exercise and self-formation. In the process of time in the present moment, concentration, attention, and focusing on the coherent and intricately changing relationship between strokes allows the frequency of the spirit to flow through the soft fibers of the painting brush, while the heights of spiritual freedom achieved by the ancients are retained in the handwriting. This is why the Zen Buddhist monk’s last words embody a lifetime of enlightenment. The Chinese tradition reaches the threshold of spiritual experience through the crafting of a single thread. It is not by chance that calligraphy became a form of life and emerged in Chinese history in conjunction with Chinese painting. It is another outlet for spiritual power built and developed on the basis of Western shapes, images and blocks of colour, an independent aesthetic system and self-training path for the mind and body, relying on the vitality and spiritual subtleties of the structure built up by the brushwork. The brushwork is also a difficult practical skill, whether in terms of self-technique, aesthetic norms, or spiritual awareness, and has become a child in the dirty water thrown out by the modernist revolution, requiring us to re-examine and treat it when we look back at tradition. The exploration of Lin Haizhong and other artists who continue to practice the brushwork opens the way for our contemporaries to access the ancients in exploring their own selves, training their minds and bodies through self-technique, and thus achieving a state of freedom.

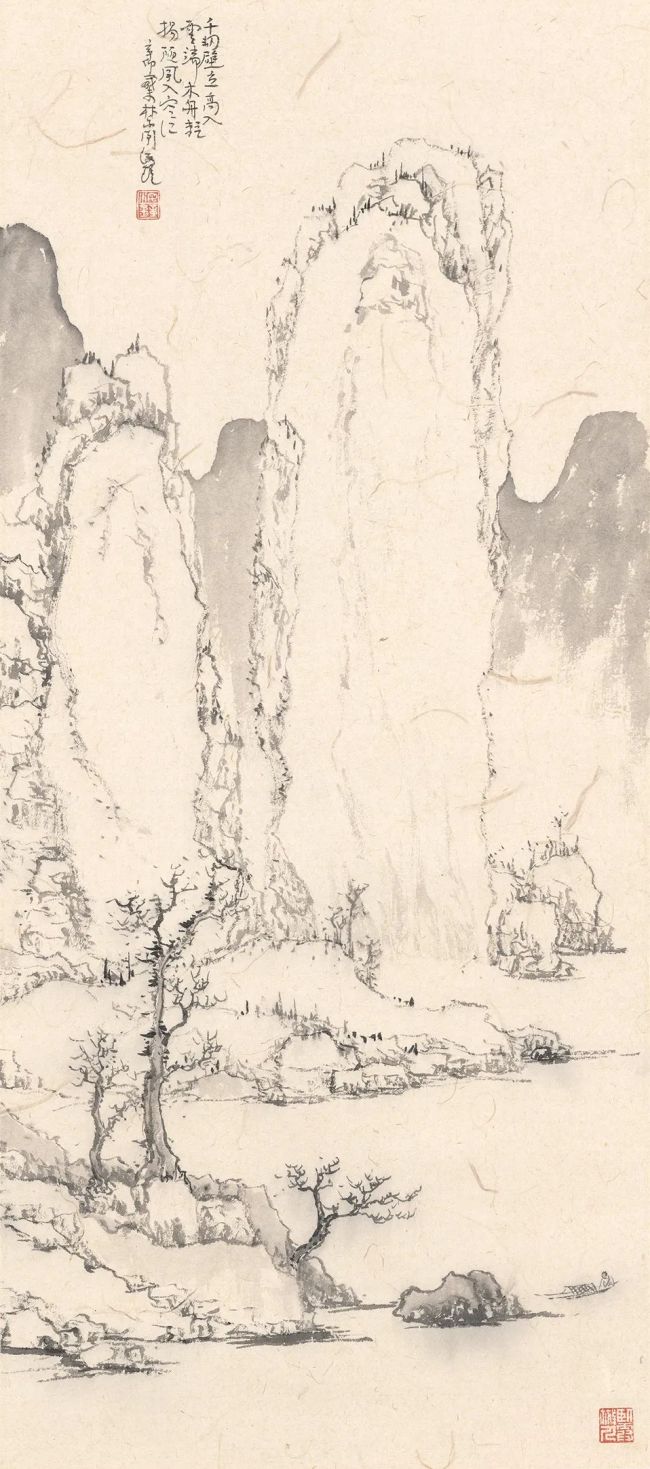

千仞壁立图纸本水墨 Ink on paper74x32cm2011