2024年对于汪鹏飞来说是起承转合的关键一年,他在做创作期间也用水彩轻松地勾画很多身边不起眼的日常之物,一个年份感的青花罐子,阿贝威士忌酒瓶、南澳岛的蚝壳、没有标签的梅子酒等等,当回到自我生命的内在体验,回到绘画本身,眼中的世界必然被抽离为一帧帧被形象充斥的图片,而一生的整体性,正是由这些微末的局部拼凑而成,像霍克尼拼贴出来的照片。

世界一直在那,好与坏,在于看与不看,在于看到什么,在于如何看以及个人与这个世界的相处之道。

(文/孙晓枫,《看,这个世界——汪鹏飞的游走和记录》,甲辰冬月完稿于南澳岛南山灶火)

Look At The World

——Wang Pengfei's Wandering and Records

Wang Pengfei is a person who possesses the rare ability to overcome his own inertia.

In his constant wanderings, he seeks transformation—both spiritual resonance and the evolution of his understanding of painting. The many places he has lived in have provided him with distinct perspectives and experiences, which he channels into his artistic endeavors. The figures, landscapes, and still lifes he depicts are not mere representations but become markers of the stages of his inner journey. They preserve the unique questions and thought processes of each phase, serving as relics left behind for both time and memory. Beneath the simplicity of these images lie nodes in time, each leaving behind a fragment of story—stories intertwined with life’s nuances and the ever-evolving discourse of art.

TheEchoes of History series andCity of Memory series, created around 2007-2009, stand as monumental works from his early period. In his thirties, with a sense of responsibility that came with age, Wang Pengfei looked back on history, feeling its energy reflected in the impassioned idealism of his youth. The echoes of history resonate deeply, their reverberations distant and profound, their former splendor now fragmented and faded. What was once a living, breathing historical space is now marked by the texture of time—humanity has receded, prosperity has vanished, and a sense of melancholic sorrow has solidified into an almost tangible shell. In crafting his depictions of this historical space-time, Wang Pengfei takes on the heavy burden of history, marching forward with it.

The style of this period is undeniably influenced by the German Expressionist master Anselm Kiefer, whose works, steeped in deep historical reflection, possess a grand vision and an aspiration toward the sublime. Kiefer’s compositions, full of spiritual tension, probe the layers of history, revealing the sudden and tumultuous eruptions buried within time’s silent corners. Wang Pengfei, too, adopts a similarly humble stance—looking upward, he places himself beneath the vast expanse of history, seeking spiritual purification and transcendence.

In a note he once wrote: “Spiritual painting is my artistic ideal. Over the years, I have used my creative practice to explore and express my understanding of spiritual painting. Simultaneously, through this process, I have continually honed and elevated my own spiritual character.” Indeed, his pursuit of heroism, romanticism, a deep sense of history, and even religiosity has led him to respond to the summons of tragic spirit. With a perspective from above, Wang Pengfei stands solitary at the center of the stage—his surroundings empty, silent. A single, powerful beam of light strikes down upon him, casting him into sharp relief.

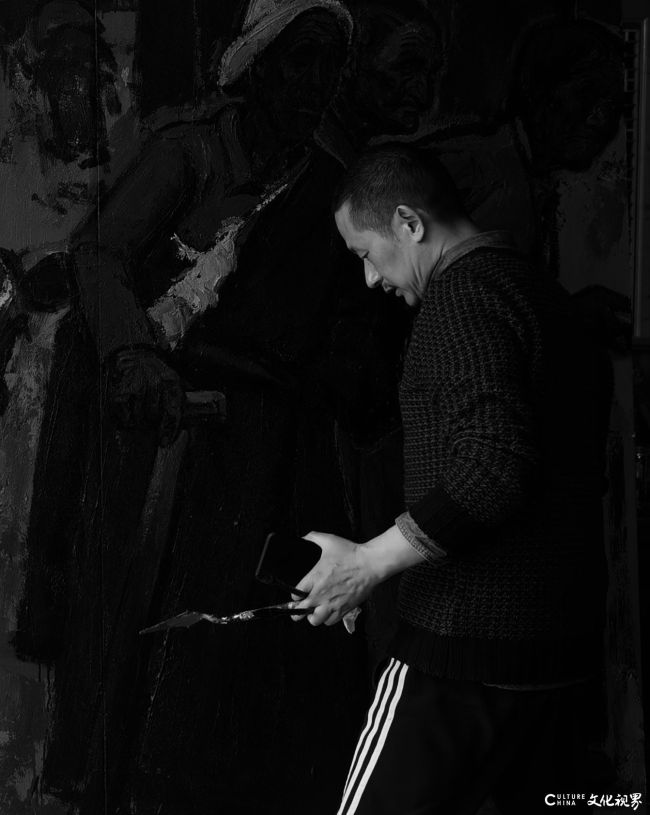

Works such asGrief,The Ancient Path of Xikou,The Iron Ox of the Yellow River, andLeifeng Tower still belong to the continuation of the artistic style and path that marked this period of Wang Pengfei’s career. The intense emotions, heavy brushstrokes imbued with a chiseled power, and the tangible texture of the paintings imbue the scenes with a monumental quality and an overwhelming sense of gravity. During this time, Wang Pengfei traveled extensively through central China and the vast Northwestern regions—he passed through Shanxi, Gansu, Shaanxi, and Henan, leaving behind a series of works in places such as the Right Guard and the Yungang Grottoes. His moments of pause and contemplation became the very essence of his creation. Wherever he went, he was driven by a deep yearning. The alien, desolate, and bitterly cold Northwestern landscape served as a forge for his spirit. Accompanied by the wind and sand, he sought a personal sense of insignificance amidst the vast historical dust. With color and brushwork, he captured the primal force of nature. The ancient cities, with their visual mass, appeared like stones fallen from the sky or emerging from the earth. In this chaotic and indistinct world, Wang Pengfei repeatedly sensed the arrival of divinity and religious presence.

From 2014 to 2024, the ten years spent sketching in Gannan became a crucial period for Wang Pengfei to deepen his themes, solidify his personal style, and refine his technical system. During this time, he frequently traveled to Gannan with Mr. Zhong Han, Mr. Li Yanzhou, and Mr. Yu Changnong for field studies. For four or five years, he even drove thousands of kilometers on his own, immersing himself in the region to document the local life, customs, and religious practices. Wang Pengfei lived alongside the people of Gannan, sharing meals and lodging, and followed the herders as they drove thousands of cattle and sheep across the landscape. He experienced firsthand the lives of those who trekked across rocky paths, their bodies long bent from years of labor, and observed the heavy, sorrowful mood that lingered in the air when herders sold their cattle and sheep at the markets. The return journey, marked by a sense of parting and abandonment, seemed to carry a weighty undertone of existential finality. The people of Gannan, with their deep Buddhist faith, saw the act of selling livestock as an indirect form ofkilling, carrying with it an enduring sense of original sin and the need for repentance. This heavy, somber awareness of sin seemed to fester within the hearts of the people. Wang Pengfei described them as having “hands like weathered tree bark,” their rough exteriors hiding the deep compassion and karmic understanding of their hearts. They embodied a profound mercy for all living beings.

For Wang Pengfei, Gannan represented an existence entirely different from the urban life in Shanghai. It created a vast tension between the environments of his native places—Shanghai and Anhui—and the unfamiliar terrain of Gannan, a tension that pulled him back and forth between two extremes. In this space, Wang Pengfei became a person on a self-directed journey. The stark contrasts between different ethnic cultures, religious beliefs, and the resulting spiritual lives, lifestyles, values, and behavioral norms created a profound sense of disparity. This dissonance in visual composition, one that was so dramatically different from his own, struck Wang Pengfei as something “surreal.” The sparsely populated ancient cities, the herding lines of nomads, the long-kneeling figures, the solemn and dignified temples, the desolate Gobi and dried-up riverbeds—all these elements unfolded slowly, like a quiet experience rooted deeply in the earth. Everything that had once been suspended in the air slowly descended into the ground. Wang Pengfei felt in the people of Gannan a quiet, grounded way of living, one that did not seek immediate rewards but found the greatest reward in simply treating life with kindness.

This specific experience of time and space often evoked a strong sense of religious emotion in him, prompting ultimate questions about life and death. During his time in Gannan, Wang Pengfei drew inspiration from the questioning spirit of Paul Gauguin’sWhere Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?and the visual composition of Jiang Zhaohua’sThe Picture of Refugees. This led him to create monumental works such as苍(Cang, 200CM x 600CM),赛马会(The Horse Race, 220CM x 1000CM), and黑白变奏曲(Black and White Variations, 200CM x 800CM), all of which explored complex arrangements of figures and scenes in which middle ground and distant views intermingled. These expansive works documented the lives of the people of Gannan and captured a unique Gannan temperament as well as the inner spiritual character of its people. Smaller works such as玛尼堆(Mani Pile, 100CM x 150CM) and转场(Transhumance, 100CM x 150CM) were also significant during this period. The former carries a religious emotionality reminiscent of Millet’sThe Angelus, with rough, sparse brushwork, while the latter captures the mass movement of cattle and sheep during the seasonal transhumance, with a visual rhythm full of formalism. In the strong contrast of white and red, the work balances the starkness and intensity of the land’s contradictions.From the Gannan series, one can easily observe Wang Pengfei’s ongoing reflections on issues of painting and language. He constantly sought new possibilities and references for his technique, a thread that runs parallel to the themes in his works.

Through years of observation, sketching, and living in Gannan, Wang Pengfei was able to closely experience the most subtle frequencies in Gannan’s existence. He used a simplified approach to portray the spirit of Gannan, taking a level gaze toward the people. All the emotions and his understanding of religious spirit were grounded in the daily lives of the local people, captured in the often overlooked details of their actions.

In 2019, Wang Pengfei began exploring digital painting. Initially, he started drawing on his phone, but later invested in an iPad specifically for his art. The convenience of digital tools allowed him to fully immerse himself in the joy of painting, offering a sense of lightness—the freedom to create anytime, anywhere, with the ability to make instant judgments. For someone passionate about painting, fragmented moments of time could be fully utilized. He could paint wherever he went, responding with keen sensitivity, and the ease of editing and revising was an attraction that led to an outpouring of works.Since immersing himself in digital painting, the heavy gray tones that defined his earlier works gradually disappeared, replaced by the brightness of sunlight, high-saturation colors, and flowing, rhythmic lines. The dynamic quality that had always existed in his artistic talent slowly emerged, and the joy of painting was rekindled. This new phase sparked fresh contemplation. However, during a road trip to Gannan with his child in 2022, some personal struggles led him to make the decision to move away from Gannan as a subject. Technology, in a certain sense, had changed his thinking, altering the way he viewed the world, the angles from which he observed it. The shift in his approach to painting and the emotional distance he felt finally led him, in 2024, to bid a complete farewell to Gannan. He longed to return to the familiar rhythm of urban life, to the people and things that surrounded him, to reconnect with the everyday, and with the sunlight.

During this period, he embraced David Hockney’s idea that “the meaning of painting shifts from the result to the process, in preserving the experience and the act of observation.” He also resonated with Hockney’s assessment of Picasso’s work: “Picasso’s uniqueness lies in how everything he painted was drawn from real life; he always sought themes from ordinary, everyday things.” This sentiment aligns deeply with Qi Baishi’s philosophy, who also mentioned that he painted only what he was familiar with. This acceptance became Wang Pengfei’s form of self-liberation, a justification for stepping away from grand narratives and the conventional standards of traditional painting. The spiritual cleansing offered by his early subjects had made painting a demanding, almost rigid endeavor. The strong sense of purpose in theme development and character shaping often diminished and constrained his personal presence within his work. Stylization easily fell into the trap of modernism and the tyranny of themes.To offer an analogy, when a work centered on Gannan is placed within the highly urbanized context of a city, the visual tension between the painting and the everyday world becomes stark. Aesthetic and psychological distances emerge, turning the work into something more akin to curiosity, to a genre painting, or a pastoral song that remains silent amidst the clamor of new cultural trends. The sense of disconnection between nomadic culture and urban culture is more pronounced than any sense of fusion. This dissonance is the product of cultural differences and the time gap in their respective developments.

In the autumn, Wang Pengfei traveled to Xishuangbanna, a tourist destination brimming with ethnic charm. Xishuangbanna served as an extension and supplement to urban culture, a composite space where city culture and ethnic traditions coexisted. The warmth of Xishuangbanna, with its gentle climate, contrasted sharply with the dusty, harsh environment of Gannan, located in the southwest and northwest respectively. This juxtaposition marked a pivotal shift in Wang Pengfei’s visual narrative, creating a significant transition in his artistic journey.

Wang Pengfei began to look around him, using oil paints to capture his students, friends, and the urban spaces they inhabited. (By this time, he had been painting on his iPad for several years.) He observed the mental states of those around him, documenting the sense of dispersal and romance that city dwellers experience amidst the convenience of modern life. He painted the loneliness and unfamiliarity that people felt in the face of the rapid pace of urban development and the overwhelming presence of multimedia information. In the summer of 2024, due to an exhibition project at the year’s end, Wang Pengfei spent over ten days doing artist residency work in Guilin. The space’s owner, Li Lanyue, who had spent years studying in the UK, had transformed the space into a miniature version of an urban environment, filled with symbols of youth culture. Amidst the clutter of these symbols and the industrial lighting, Wang felt a surge of creative impulse. He conversed with those coming and going through the space, painting portraits of Xiaoju, Zheng Long, and Yibai. These portraits not only served as a record of the space but also helped him tackle the challenge of simplifying and serializing the urban theme. In this relatively enclosed space, the interactions of city people were mirrored, while the sense of alienation and estrangement that often follows personal connections remained preserved. The unfinished spaces in his work represented both an emptiness and a lingering suspense.

The year 2024 became a key turning point for Wang Pengfei, a year of transitions and new directions. During his creative process, he also casually sketched everyday objects around him in watercolor—an old blue-and-white porcelain jar, an Ardbeg whisky bottle, oyster shells from Kangaroo Island, a bottle of plum wine without a label. Returning to the inner experience of his own life, returning to painting itself, the world in his eyes was inevitably reduced to frames of images, each filled with shapes and forms. The overall unity of life, he realized, is pieced together from these seemingly insignificant details—like a collage of photographs, as David Hockney had once done.

The world has always existed, in both its beauty and its flaws. Good or bad, it depends on whether we perceive it or not, and what we choose to perceive, how we see it, and the manner in which we choose to coexist with it.

(Sun Xiaofeng,Written in the winter of Jiachen Year, on the southern hill of Nanshan, Kangaroo Island)

(来源:角一)

策展人简介

孙晓枫,独立艺术家、策展人、写作者和游食者。

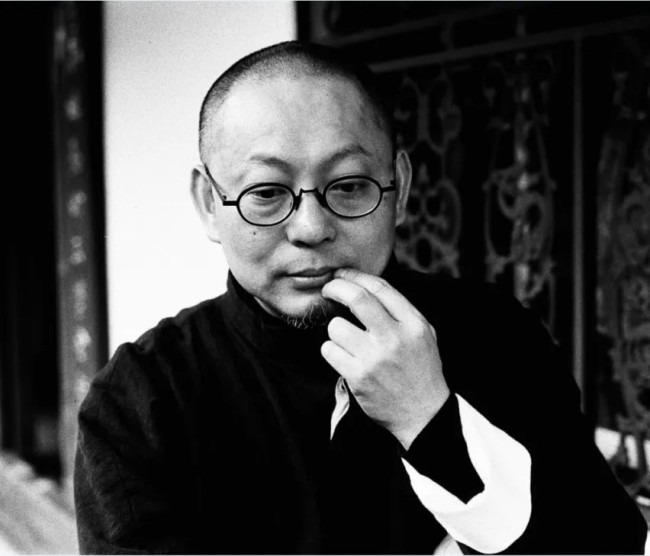

画家简介

汪鹏飞,安徽省歙县人,现任教于广西艺术学院美术学院油画系,硕士研究生导师。国家一级美术师,中国美术家协会会员,70油画公社社员。

2006年毕业于中央美术学院油画本科

2007年结业于中央美术学院油画系助教研修班

2012年结业于中央美术学院油画高研班

2016年毕业于中央美术学院油画系,获艺术硕士学位